the richest person in our family—spotted the two of us and asked, “Why aren’t you back at the house on Hawthorne Street?” I froze. “What house?” Three days later, I walked into a family gathering—and my parents stopped cold, the wineglass in my father’s hand slipping down…

If you’ve never tried to get a six-year-old ready for school while living in a family shelter, I can summarize the experience for you. It’s like running a small airport, except the passengers are emotional, the security line is shame, and you’re doing it all with one sock missing.

That morning, Laya’s sock was the one missing.

“Mom,” she whispered, the way kids do when they’re trying to help you not fall apart. “It’s okay. I can wear different socks.”

She held up one pink sock with a unicorn and one white sock that used to be white. I stared at them like they were evidence in a crime scene.

It’s a bold fashion choice,” I said. “Very ‘I do what I want.’”

Laya smiled, and just like that, for half a second, I forgot where we were.

Then the shelter door opened behind us and the cold slapped me back into reality.

We were outside St. Brigid Family Shelter. 6:12 a.m. The sky was still a bruised gray over the Portland skyline. The sidewalk was damp. The air had that winter smell, metallic and clean, like the world had been scrubbed too hard.

Laya adjusted her backpack, which was bigger than she was. I tugged the zipper up on her puffy coat and tried not to look at the sign above the entrance.

FAMILY SHELTER.

It wasn’t even the word “shelter” that got me. It was the word “family.” Like we were a category. Like we were a label on a box.

“Okay,” I said, forcing brightness into my voice. “School bus in five minutes.”

Laya nodded. She was brave in a quiet way that made me feel both proud and guilty at the same time.

Then she asked softly, “Do I still have to say my address when Mrs. Cole asks?”

My stomach clenched. “I don’t think she’ll ask today,” I said.

Laya didn’t push. She just looked down at her shoes and then back up at me, like she was memorizing my face, like she was checking if I was still me.

“Mom,” she said. “Are we going to move again?”

I opened my mouth and nothing came out.

And that’s when a black sedan slid to the curb like it belonged there. Not a taxi, not an Uber, not the kind of car that ever pulled up to St. Brigid unless it took a wrong turn and regretted it.

The door opened and a woman stepped out in a tailored coat the color of midnight, the kind of coat you see in downtown boardrooms, not outside shelters.

Evelyn Hart, my grandmother.

I hadn’t seen her in over a year. I knew that because my life had been measured in “before everything fell apart” and “after,” and she belonged firmly in “before.”

She looked exactly the way she always did—composed, elegant, and slightly terrifying. Not in a cruel way. In an I-once-ended-a-boardroom-argument-by-raising-one-eyebrow way.

Her gaze landed on me first, and I saw recognition, then confusion. Then it landed on Laya. Something changed in her face. Something quick and sharp, like a crack in glass.

She looked up at the sign above the entrance, and then she looked back at me.

“Maya,” she said, and my name sounded strange in her voice, like she hadn’t said it out loud in a long time. “What are you doing here?”

My first instinct was to lie, not because I thought she’d judge me, but because I couldn’t stand being seen.

“I’m fine,” I said, which is the default lie of exhausted women everywhere. “We’re okay. It’s temporary.”

Evelyn’s eyes flicked down to Laya’s mismatched socks and then to my hands, red and dry from too much sanitizer, too much cold, too much life.

Her voice went quieter. “Maya,” she said again. “Why aren’t you living in your house on Hawthorne Street?”

The world tilted.

I blinked at her. “My what?”

She didn’t repeat herself like she thought I was stupid. She repeated herself like she thought I might faint.

“The house,” she said, enunciating the words. “On Hawthorne Street.”

My heart started pounding so hard I could feel it in my throat.

“What house?” I heard myself say. “I don’t have a house.”

Evelyn stared at me as if I’d spoken in another language. I could see the calculation behind her eyes. She was running numbers in her head—timelines, possibilities, lies.

Laya tugged my sleeve. “Mom,” she whispered. “Do we have a house?”

I looked down at her. Her eyes were wide, hopeful in a way that hurt.

I swallowed. “No, honey,” I said gently. “We don’t.”

Evelyn’s face went very still, and when my grandmother went still, it usually meant something was about to break.

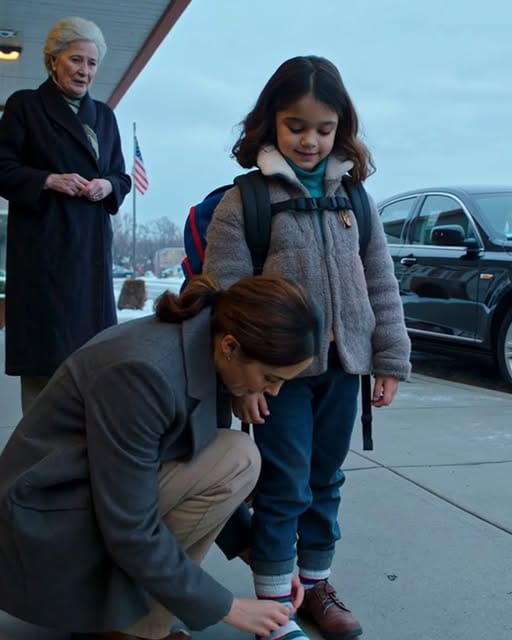

She stepped closer. Not to me. Toward Laya.

She crouched down in front of her, which was almost shocking. Evelyn Hart did not crouch for anyone. She sat in chairs that cost more than my monthly income and made everyone else adjust. But there she was, lowering herself to my daughter’s height.

“You’re Laya, right?” she asked.

“Yes,” Laya whispered shyly.

Evelyn’s expression softened just slightly. “That’s a beautiful name.”

Then her eyes lifted to mine and turned sharp again.

“Get in the car,” she said.

I blinked. “Grandma—”

“Get in the car,” she repeated, and there was no room in her tone for negotiation.

I felt heat rush to my face—anger, embarrassment, relief, everything tangled up.

Evelyn opened the back door of the sedan. I hesitated. Laya looked up at me.

“Mom,” she said, small and steady. “It’s okay.”

And the fact that my six-year-old was comforting me was the final straw.

I nodded. “Okay.”

Laya climbed into the back seat first, clutching her backpack, and I slid in beside her, still half expecting someone to tap me on the shoulder and tell me this was a misunderstanding. As soon as the door shut, the silence inside felt expensive.

Evelyn didn’t drive immediately. She just sat there with both hands resting lightly on the steering wheel, staring straight ahead.

Then she spoke, very calmly.

“By tonight,” she said, “I will know who did this.”

My stomach flipped. She turned her head to look at me. I swallowed hard.

“Grandma, I don’t understand.”

“No,” she said. “You don’t. And that tells me everything.”

She pulled out her phone, tapped once, and said, “Call Adam.”

A man answered quickly.

“Mr. Miles, this is Evelyn,” she said. “Get the property manager for Hawthorne Street on the line, and I want a simple answer. Who has the keys? Who is living there? And whether anyone has been collecting money off it.”

My blood ran cold.

Money.

I stared at her profile, at the set of her jaw, at the calm way she said those words like she was ordering coffee. And I realized I was not just embarrassed. I was standing on the edge of something much darker.

If you’d asked me six months earlier if I thought I’d ever be living in a shelter with my daughter, I would have laughed. Not because I thought it couldn’t happen. Because I thought it couldn’t happen to me.

That’s a dangerous kind of arrogance, by the way. It doesn’t protect you. It just makes the fall louder.

Six months earlier, I was still working as a nursing assistant at St. Jude’s Medical Center downtown. Twelve-hour shifts, call lights going off like a slot machine, people asking me for things I didn’t have. Time. Answers. Miracles.

I was exhausted, but I was surviving.

And then I moved in with my parents.

It was supposed to be temporary. It always starts with temporary.

My dad, Robert, had that calm, reasonable voice that people believe. My mom, Diane, had that soft smile that made her sound like she was doing you a favor even when she was cutting you off at the knees. These days, I call them by their first names. “Mom” and “Dad” didn’t fit anymore.

“You can stay with us until you get back on your feet,” Diane said. “Laya needs stability. Family supports family.”

I should have heard the fine print hiding in that sentence. But I didn’t.

At first, it was tolerable. My parents’ apartment was small, but we made it work. Laya slept in my old room. I worked. I paid what I could. I kept my head down.

Then the comments started.

Not big, obvious attacks. Little ones. The kind that don’t look like cruelty if you tell someone about them later.

“You’re always tired,” Diane would say. “Maybe you should organize your life better.”

Robert would sigh when Laya’s toys were on the floor. “We’re just trying to keep the place nice.”

And then one night, after I’d come home from a double shift with my feet aching and my brain half-dead, Diane sat down at the kitchen table like she was about to deliver a diagnosis.

“We need to talk,” she said.

I already knew that tone.

“We think it’s time you became independent,” she said softly. “You’ve been here long enough.”

“I’m trying,” I said, keeping my voice even. “Rents are high, deposits—”

“You’re a mother,” Diane said. “If you’re a good mother, you’ll figure it out.”

The words hit me so hard I actually looked around like someone else must have said them.

Robert cleared his throat. “Thirty days. That’s reasonable. We’re not monsters.”

I wanted to scream, but screaming never helped in that apartment. It just gave them something to point at later. So I nodded.

“Okay.”

And I tried.

I looked at listings during my breaks at the hospital, my thumbs scrolling while I gulped cafeteria coffee. I called places. I got told the same thing over and over.

First and last month. Deposit. Proof of income. Credit check. Sorry, we chose another applicant.

Every day I felt like I was running uphill with Laya on my back.

And then came the night they decided thirty days was actually a suggestion.

It was after a late shift. I’d helped a confused elderly man back into bed three times, cleaned up a spilled tray, and held a woman’s hand while she cried because she was scared of surgery.

I came home after midnight. The hallway light outside my parents’ apartment was on. My stomach tightened immediately.

Two cardboard boxes sat outside the door. My boxes.

I stared at them for a long second like my brain refused to accept the shape of what I was seeing. Then I tried the doorknob.

Locked.

I knocked.

Silence.